Background

Research on certified community behavioral health clinics (CCBHCs) suggests reimbursement approaches may impact the CCBHC workforce. One of the federal programs available to CCBHCs – the Section 223 Demonstration Program – requires Medicaid reimburse CCBHCs in 10 participating states using a daily or monthly prospective payment for Medicaid beneficiaries. Early research finds that CCBHCs participating in the Section 223 Program hired more staff and had higher caseloads than CCBHCs not participating in the Demonstration. No research has examined alternative payment models (APMs) contracted by non-Demonstration CCBHCs and APMs between CCBHCs and non-Medicaid payors.

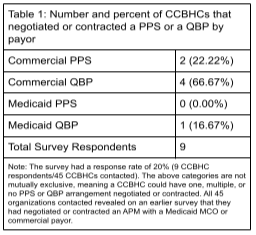

In 2021, the BHWRC partnered with the National Council for Mental Wellbeing to field a survey on the types and designs of APMs between CCBHCs and Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and commercial payors. Table 1 presents the number of CCBHCs that had negotiated or contracted a prospective payment system (PPS) or quality bonus payment (QBP) by payor type.

In this project, we build upon this research by (i.) fielding a similar survey to gather longitudinal data on the number and design of CCBHC APMs and (ii.) interviewing CCBHCs that responded to last year’s survey about the structure of their PPS and QBP arrangements and the processes involved in negotiating and contracting APMs.

The findings from this project can be used by CCBHCs interested in establishing their own APMs. It will provide insights on the types of APM structures currently negotiated or contracted between CCBHCs and MCOs and commercial payors. It will also highlight facilitators and barriers to negotiating APMs and potential solutions to addressing these challenges.

Aims & Research Questions

This project employs a mixed methods study design that uses quantitative survey data to capture descriptive information on the number and design of APMs followed by a qualitative analysis of the processes involved in negotiating and structuring APMs. We ask the following:

- How many CCBHCs have negotiated or contracted APMs with Medicaid MCOs and commercial payors?

- What is the structure of APMs between CCBHCs and MCOs and commercial payors?

- What is the negotiation process leading to an alternative payment arrangement between a CCBHC and an MCO and commercial payors?

Findings

Our analysis reveals that approximately one-third of survey respondents were receiving payment through an APM. Grantee-only CCBHCs were the least likely of all respondents to have established arrangements. This may signal that receiving the Medicaid special payment through the Demonstration, SPA, or waiver may provide CCBHCs critical experience in implementing APMs. The data also provide a correlation between CCBHC size and APMs. The largest CCBHCs—both measured as the number of clients and employees—were the most likely to have CCBHCs in comparison with small- and medium-sized clinics. It is possible that larger organizations have more administrative capacity and/or experience in designing and implementing APMs than their peers in smaller organizations.

While more than two-thirds of APMS cover the required crisis mental health services, only 45% of grantee-only CCBHCs include these required CCBHC services. Policymakers and advocates alike have discussed relying on CCBHCs to support 988 implementation. In light of the likely projected increase in call volume associated with 988, grantee-only CCBHCs may consider prioritizing inclusion of crisis intervention services when negotiating APMs to support their delivery of crisis services.